LYSE DOUCET (CÔTE D’IVOIRE 1982)

I was sitting with a group of African women pounding yams. Day in day out, they pounded yams. Then, one day, I finally asked: “Wouldn’t you like to do something different?” They stole a glance at each other, and at me, and laughed and laughed. “What kind of question is that? We can’t do anything else. So why would we ask?”

It was one of my first lessons as an aspiring journalist in trying to understand a society on its own terms. It shouldn’t be my questions, never mind the answers. It was their questions that matter.

My Crossroads experience in 1982 changed the direction of my life. It was the catalyst that propelled me into the international work I do to this day.

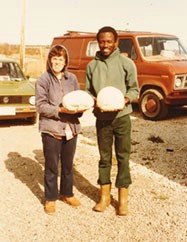

My placement was in the town of Adzope, at a small private school set in lush tropical forests a short drive from the Ivorian capital, Abidjan. It was my first trip abroad. I am grateful to this day that I started my journey at village level. It gave me a window on a world so different from my own.

Whenever I do journalism training, I recall my own beginnings in an African village which taught me that to truly understand a society, you must try to feel its “heat and dust,” the rhythms of its days. Life at an Adzope school with two fellow Crossroaders was endlessly interesting, absorbing and an occasional challenge!

When my placement ended, I travelled across West Africa to Senegal where I started freelancing as a journalist where I got my first article published in 1983 in “West Africa” magazine. I ended up spending five years in Africa, and my Crossroads experience in those first months shaped my understanding of the continent. It’s a badge of honour when I return to Africa for my work, or meet Africans abroad.

Two years ago, I returned to Adzope. It was bittersweet to walk the paths I had taken so long ago and to see the sad turn Ivory Coast had taken from a beacon of stability to a divided land. Even our much-loved representative there, Tete Kpakote, had to flee the violence.

Each time I visit Canada, I am reminded of how these cultures we discover in our Crossroads placements are now part of our own national mosaic. They present a richness and a responsibility within our own neighbourhoods. More than ever, it seems critical for us to try to understand differences in cultures and attitudes. This is where Crossroads also plays a role.

I will remain forever grateful for my Crossroads experience, a defining moment that opened my eyes to the world, starting with my first meetings with Crossroaders in Toronto. They had such optimism and curiosity. I’ve stayed in touch with my fellow travellers. And in the world I live in now, interviewing everyone from peasants to presidents, I appreciate my connection to the Crossroads community and its commitment to a better world.

Lyse Doucet is a presenter and correspondent for both BBC World Service radio and BBC World News television. She began her journalism career following her Crossroads placement and was based in Abidjan for five years as a foreign correspondent for the BBC. She often anchors special news coverage around the globe and has frequently interviewed world leaders. Her reporting has earned her numerous broadcasting awards. Lyse is an honorary patron for Canadian Crossroads International.